Can Services Drive Growth?

ICT technologies promise to transform services—but can it replace manufacturing as a new growth engine?

Manufacturing has long been the primary growth driver among lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs). From the U.S. and Germany to the East Asian Tigers to, most recently, China, prowess in manufacturing has led to miracle growth spurts. However, new scholarship shows that the peak share of manufacturing in value-added and employment in today's LMICs is lower than that of their high-income precursors.1 In other words, LMICs are deindustrializing before they can establish a mature industrial sector, suggesting that manufacturing may no longer provide the same growth opportunities that it once did.

Can services-led growth offer similar development benefits? Conventional wisdom says that manufacturing is the best way for a country to develop because it generates productivity growth and large-scale job creation. Manufactured products can also be consumed separately from where they are produced, making them suitable for the export-led growth strategies that fueled the growth of the East Asian Tigers.

Lacking these qualities, the service sector is not conventionally considered a serious development engine. However, in a 2021 book by the World Bank Group, Nayyar et al. argued that technological advances from the ICT revolution can overcome the limitations associated with services and transform services into a viable development engine.2 At the heart of Nayyar et al.’s book is the idea that ICT-enabled services can generate the twin benefits of productivity growth and employment expansion that manufacturing has historically provided to early developers. I’m pretty skeptical about all this. In this post, I’ll explain why. But first, let’s address why the service sector has been given a bad name and new optimism over services in the ICT age.

The problem with services

Traditionally, services are thought to be limited in delivering growth because 1) services are simultaneously produced and consumed, 2) service-related labor has intrinsic value, and 3) services have limited linkages to other economic activities.

The simultaneity of consumption and production means that within-sector productivity gains are more challenging to achieve because the efficiency of services is limited by the time it takes customers to consume the service. For example, a restaurant’s efficiency can only be so high before needing its customers to dine faster. This also means that, unlike manufacturing, services do not benefit from economies of scale or scope (e.g., scaling up the restaurant would require a proportional increase in service staff). Moreover, the fact that services are produced and consumed simultaneously means that they cannot be stored or transported, making them non-tradable and bound by physical proximity. This is especially problematic for developing countries because domestic demand tends to be (relatively) weak and investment (relatively) constrained. This means that the service sector cannot benefit from across-sector productivity gains to the same extent as manufacturing, as it cannot absorb unskilled, rural labor to the same extent.

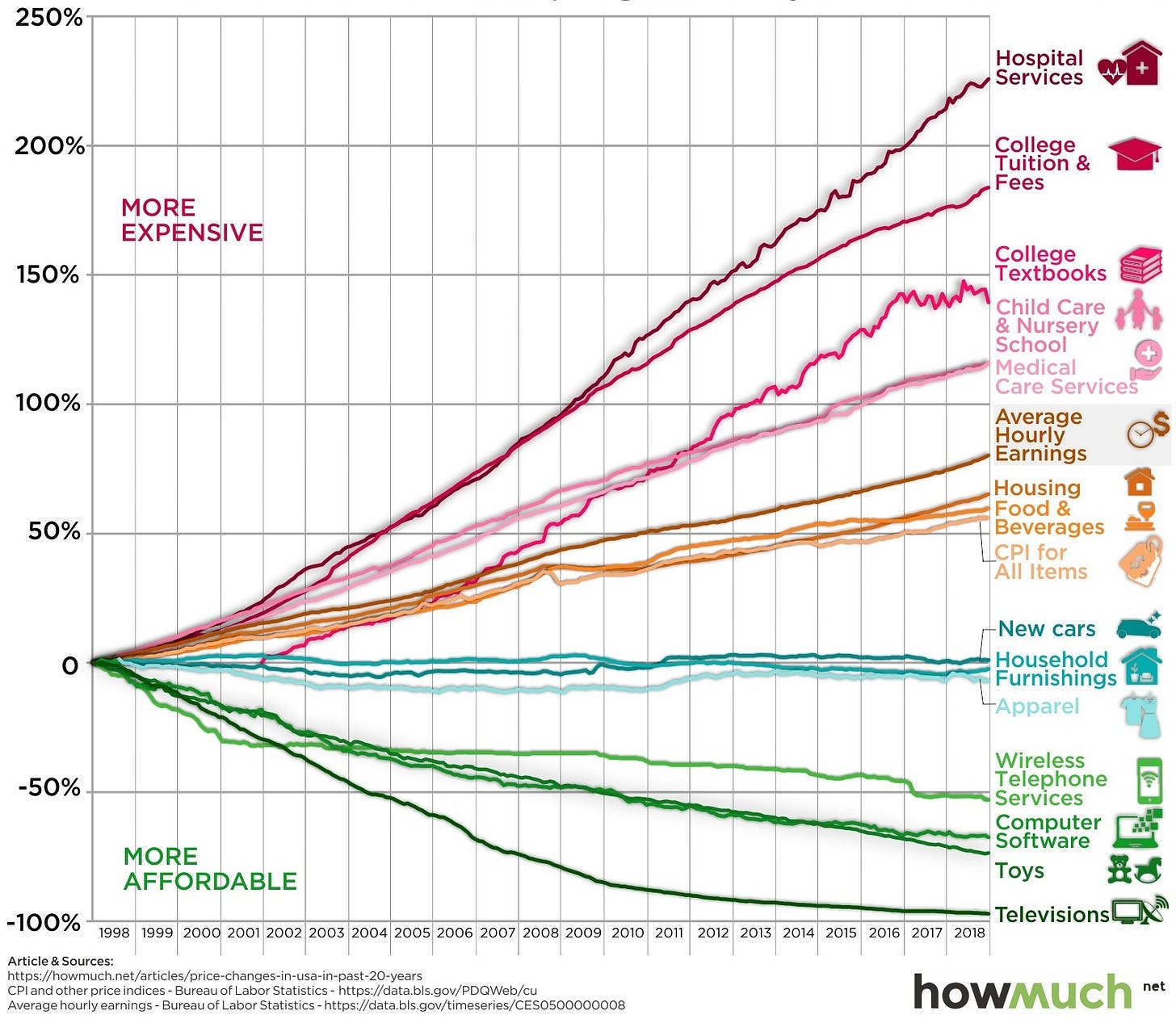

Economist Baumol argued that it is difficult to increase the productivity of services through capital accumulation, innovation, or economies of scale because labor is not a means to an end but an end itself. In other words, the labor involved in services has intrinsic value. Baumol classic example was that it took a string quartet exactly the same amount of time to play a Mozart piece in 1965 as it did in 1865, so despite technological advances happening elsewhere in the economy, the productivity of the string quartet didn’t increase. This insight is at the heart of Baumol's "Cost Disease" theory, which argues that, in a world of technological progress, we should expect the cost of manufactured goods to fall and the cost of labor-intensive services to rise.

Finally, there is the question of linkages and complementarities. As I’ve explained in a previous post, manufacturing has a unique ability to induce forward and backward linkages and investment in complementary capabilities. For instance, investment in a tire factory would induce investment in upstream industries like synthetic rubber production as well as downstream industries such as automobiles. These investments would also generate political pressure for state agencies to invest in infrastructure such as ports, roads, railroad systems, and electric power, without which these industries could not function. Services, by contrast, often begin and end with the interaction between producers and consumers, so supply chains are compressed, and spillovers are limited.

ICT-enabled services

Do the technologies of the ICT age allow services to overcome the limitations mentioned above? Nayyar et al.’s Work Bank book argues they do. They argue that digital electronic content makes services storable, codifiable, and transferable, allowing the production and consumption of services to be separated. This separation means that ICT-enabled services also become tradable, such that developing countries can export services and tap into the consumer markets of more advanced countries. Through digital technologies, services can also be scaled up so that a single producer can service multiple consumers simultaneously, thereby increasing labor productivity.

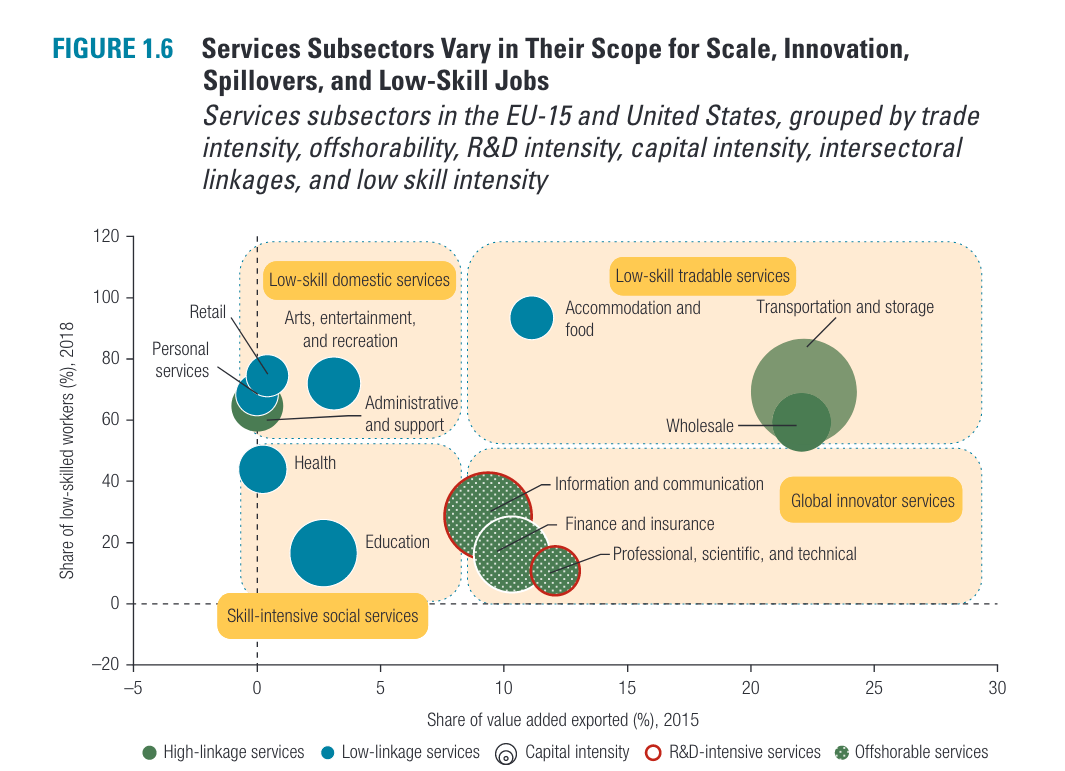

Part of their argument is that the ICT era has given rise to services in information and communication, finance and insurance, and professional, scientific, and technical sectors—a broad category they call “global innovator services.” This high-end category of professional services, they argue, has tremendous potential for within-sector productivity gains. These services deal in knowledge-based production that can benefit from scale, innovation, and spillovers—even more so than manufacturing.

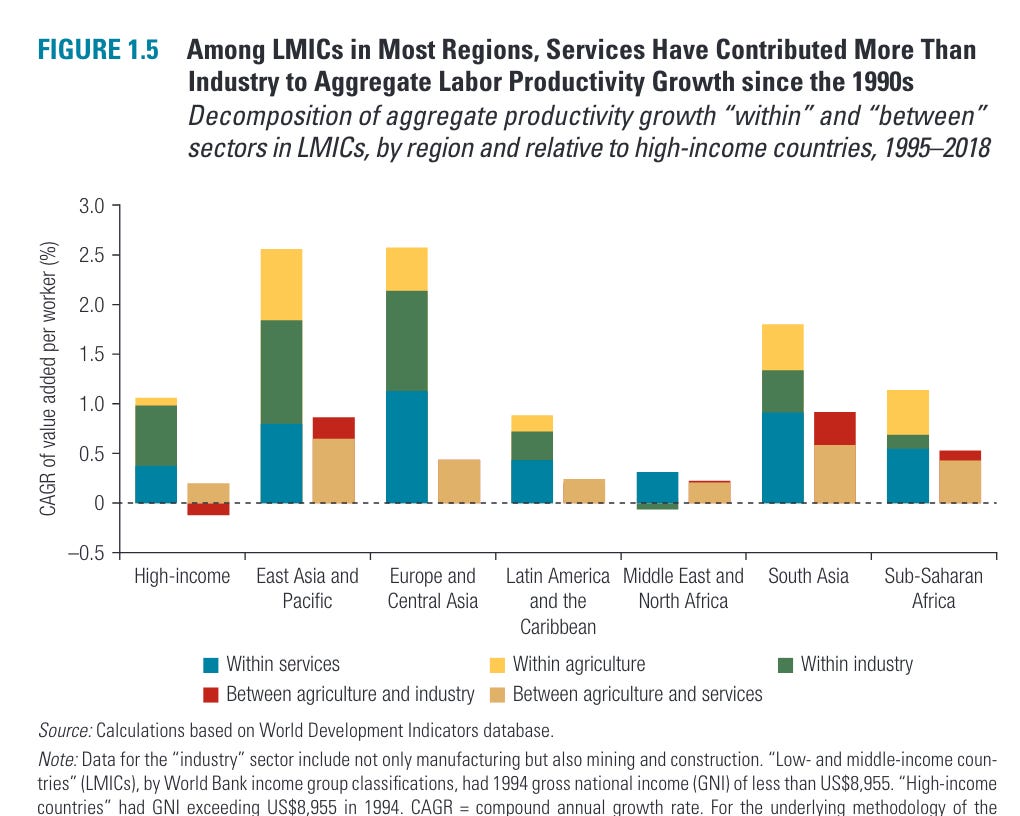

At the low end, they also point out that job creation in the ICT era is concentrated among low-skilled services, making it ideal for absorbing surplus rural labor and producing the same across-sector productivity gains that manufacturing provided to early developers. These changes in services, they claim, are reflected in the data. Since the 1990s, productivity gains among LMICs have come primarily from services rather than manufacturing—except for the case of the East Asian countries. In charting within- and across-sector productivity gains (see figure below), they find that productivity increases within-sector are highest in the service sector for most LMICs and that most across-sector gains are from agriculture to services rather than manufacturing.

This figure, however, is misleading. When it comes to across-sector change, the fact that more gains are going from agriculture to services than manufacturing shouldn’t be read as an indicator of the long-term viability of services to increase labor productivity. Given the low levels of labor productivity in agriculture, any movement away from agriculture will likely produce meaningful productivity increases.

Misguidedly technoutopian

At the heart of the problem of an ICT-enabled service sector is employment. While ICT technologies can create many low-skill jobs in the service sector, making it good for absorbing rural labor and achieving across-sector productivity gains, it is extremely challenging to increase the productivity of these jobs. For instance, customer service agencies may create jobs, but increasing the number of customers an agent can service is extremely challenging past a certain threshold. Moreover, there are no benefits to economies of scale to such work, limiting the potential for productivity gains. Instead, where productivity gains are concentrated is in the global innovation sector. However, this subsector requires high-skilled workers, making it accessible only in high-income countries.

In this way, services in the ICT era are bifurcated between low- and high-skilled workers, making it extremely hard to establish a virtuous economic and social development loop required for long-term development. The platform economy is emblematic of this dynamic. While the platforms themselves are built by a small elite group of engineers, the value of these platforms often relies on an army of precarious and non-standard gig/platform work.

The other promise of the service sector in the ICT era is that digital technologies can turn services into exportable commodities (think of online courses where the “service” of providing a lecture is being digitized and exported). If developing countries can generate these exportable services, they will, in theory, be able to tap into the consumer markets of more advanced countries.

This perspective has two problems. First, most services that lend themselves well to exports require high-skill workers, which disadvantages LMICs where a smaller supply of high-skill workers is available. While ICT also enables low-skill service sector exports, such as customer services, these subsectors offer little productivity gains for the domestic economy and limited spillovers. In the case of customer services, exports are also restricted to countries that speak the same language as those they are exporting to (i.e., customer service reps for English-speaking countries are usually located in the Philippines or India due to the availability of English speakers).

Second, the development of high-skill service exports would be extremely challenging in LMICs, not only because of a lack of skills but also because these service exports would be in direct competition with the service exports of advanced countries. In this way, the development stage of service-importing countries is critical. Previous manufacturing-led developing countries emerged when early developers were starting to deindustrialize, allowing them to seize the manufacturing markets of these early developers. Today, it would be extraordinarily challenging for LMICs to repeat this export-led growth strategy with services because they must compete against their high-income counterparts who, since deindustrializing, are also investing in services. Just imagine a LMIC country developing a search engine (an exportable service) to compete against companies like Google for U.S.-based customers.

Concluding thoughts

My perspective is not that services are unimportant and an illegitimate source of growth. In fact, I believe that the line between services and manufacturing is increasingly blurred, especially in high-end manufacturing sectors where services (such as professional IT or cloud services) are a critical part of the manufacturing process. However, these complex production schemes that combine services and manufacturing tend to only be available to high-income countries because of their demanding physical and human capital requirements.

Instead, my critique is of a purely services-led growth model, such as the one described in Nayyar et al.’s Work Bank book. Where the conventional development path begins with agriculture, then industry, and finally services, today’s developing countries are prematurely deindustrializing—skipping past industry to services faster than the early developers did. Has this produced good outcomes for developing countries? As far as I know, the answer is no. No significant prematurely deindustrialized economy has achieved growth remotely close to the likes of the manufacturing-led East Asian Tigers of the 1970s/80s.

What can developing countries do instead? There’s no easy one-size-fits-all answer, but abandoning manufacturing shouldn’t be so quickly recommended. Arguing that an ICT-enabled service sector is the future of development is misguidedly technoutopian.

Rodrik, Dani. 2016. “Premature Deindustrialization.” Journal of Economic Growth 21(1): 1–33. doi:10.1007/s10887-015-9122-3.

Nayyar, Gaurav, Mary Hallward-Driemeier, and Elwyn Davies. 2021. At Your Service?: The Promise of Services-Led Development. The World Bank. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-1671-0.