The Value of Manufacturing

Why has manufacturing historically had a unique capacity to drive economic development?

A specter is haunting us—the specter of productivism. After years of liberalization, major national players are now prioritizing production and investment over finance and digital platforms. In the U.S., Biden’s new industrial policy packages—the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS and Science Act—are a clear attempt to revive the country’s manufacturing base. In China, high value-added manufacturing and a focus on “hard tech” (as opposed to software-based production) have become the motivating force of the country’s economic engine.

There are many explanations behind this shift—green manufacturing to accelerate decarbonization, supply chain resilience in the face of geopolitical tensions, a backlash to the neoliberal period… But underlying these rationales is a time-tested wisdom, often overlooked in an era dominated by ICT and intangibles: manufacturing has a unique capacity to drive economic growth. This wisdom has even been enshrined into (Kaldor’s first growth) law. The historical evidence is compelling. From the early industrializers like the U.S. and Germany to the East Asian developmental states (Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan), and most recently, China, manufacturing has consistently spurred rapid productivity growth, enabling countries to climb the value chain and lift themselves out of poverty.

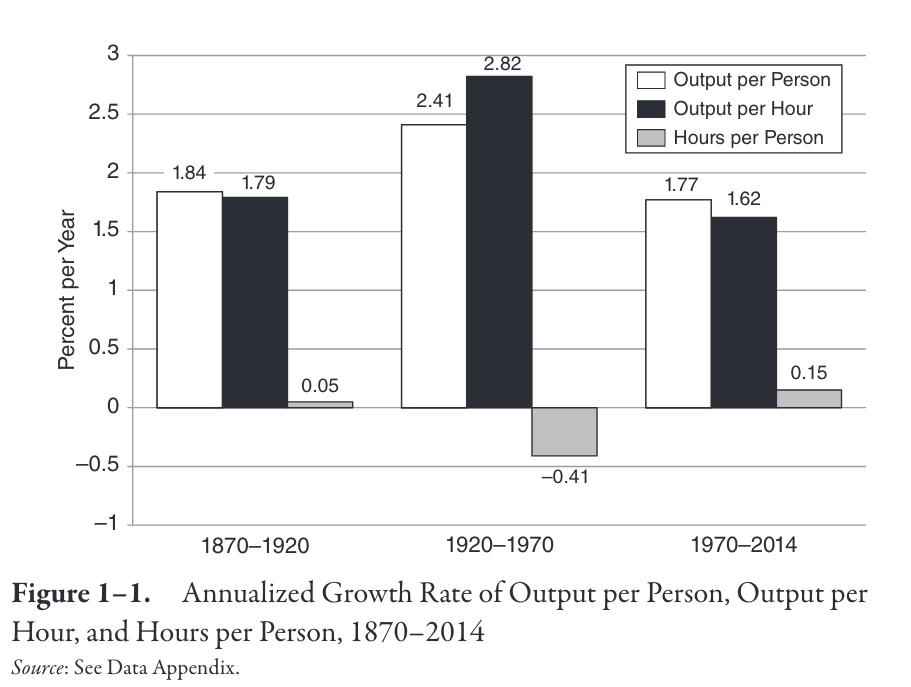

Growing up in an era dominated by financial and IT services and spending the first part of my career as a software engineer, I was naturally inclined to believe that economic progress was marked by a secular trend toward intangible and knowledge-based services. However, if growth is a function of labor productivity, then there seems to be no conclusive evidence that the trend toward ICT and intangibles has produced meaningful gains in labor productivity compared to previous eras. Development economist Robert Solow famously remarked, “You can see computers everywhere but in the productivity statistics.”1 Decades later, with data in hand, Robert Gordon confirms this observation, demonstrating that the U.S. experienced a sharp decline in labor productivity (see below) precisely as financial and IT services rose to prominence.2

A key reason, as shown on the graph, is that the middle period saw a decline in work hours per week, partly due to New Deal legislation and the empowerment of labor unions. However, the primary claim of Gordon’s book is that the inventions of the middle period—the golden years of American manufacturing—were simply more economically transformative than the financial and IT inventions of the third period.

Why was labor productivity during U.S. manufacturing’s golden years so hard to beat? And are these benefits generalizable to other countries? Let's turn to development economics to understand the pro-developmental characteristics of the manufacturing sector. I’ll note up front that just because manufacturing worked historically, there’s no guarantee that it’ll work again in the 21st century. There’s also no guarantee that it’ll work for advanced countries trying to rebuild their manufacturing base. After all, capitalist production has changed in several important ways that may undermine the pro-developmental characteristics of the manufacturing sector—but that’ll have to be a post for another day. In this post, we’ll focus on why manufacturing worked in the past. At the very least, that should give us some clues as to whether the service sector (and professions like software engineering) can take its place and whether a resurgence in manufacturing is likely to work again in the new productivist era.

Across- and within-sector productivity gains

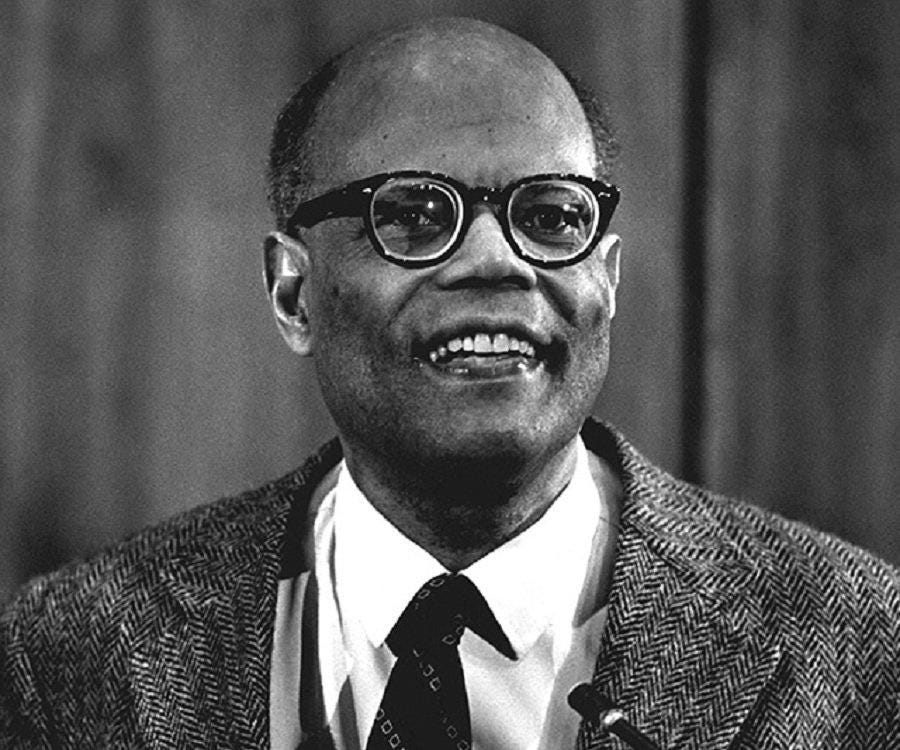

Manufacturing has served as an important first step up the ladder of economic development because of the sector’s ability to absorb unskilled rural labor and generate across-sector productivity gains—an insight first articulated by development economist Arthur Lewis. Lewis’s most famous idea, now known as the Lewis model, is the dual-sector model of development, which he articulated in 1954 in his seminal piece “Economic Development and the Unlimited Supply of Labor.”3

Its core argument is that the movement of labor from the traditional (subsistence) sector to the modern (manufacturing) sector drives economic development because the abundance of unskilled labor in the traditional sector ensures an unlimited labor supply to the modern sector. Prolonged access to cheap labor also keeps wage increases in the modern sector low, allowing surpluses to be generated and re-invested.4 China’s economic development is emblematic of the Lewis model. With a massive rural population, China’s industrial development has been fueled by the surplus of cheap migrant laborers that keep industrial wages low.

Manufacturing also generates significant within-sector productivity gains. Unlike other sectors, manufacturing industries exhibit strong tendencies of unconditional convergence in labor productivity, regardless of policy/institutional arrangements.5 This means that manufacturing labor productivity in developing countries tends to catch up with those in high-income countries and eventually converge with the global productivity frontier. Why do manufacturing sectors and not others exhibit unconditional convergence in labor productivity?

Part of the reason is that manufacturing typically deals with tradable goods, which are subject to export discipline.6 Global markets for tradable goods are inherently more competitive than domestic ones, forcing manufacturers in developing countries to enhance their productivity—or risk going under—when operating in export markets and competing directly with counterparts from more advanced economies. By contrast, non-tradable sectors face less pressure to increase labor productivity since they are not subject to export discipline (e.g., agricultural productivity in one country isn’t disciplined by those of another).

Relatedly, manufacturing production benefits from economies of scale and scope. Because manufacturing tends to have high fixed costs, these costs, when spread over a large volume of output, reduce the per-unit cost as production increases, thereby achieving economies of scale. Manufacturers often also use the same processes or inputs to produce a variety of products, leading to cost efficiencies through shared resources, thereby achieving economies of scope. For example, in the textile industry, producing larger quantities of fabric allows manufacturers to lower costs by purchasing raw materials in bulk and optimizing machine usage (economies of scale).

At the same time, the same machinery and inputs can be used to produce a variety of fabrics and garments, such as clothing, rugs, or bags (economies of scope). By contrast, the service sector cannot achieve economies of scale because scaling up often requires proportional increases in labor. Similarly, the primary sectors, including mining and agricultural production, do not benefit from economies of scope because they focus on extracting or cultivating specific resources that cannot be repurposed to create different outputs, limiting the ability to diversify production efficiently.

Forward and backward linkages

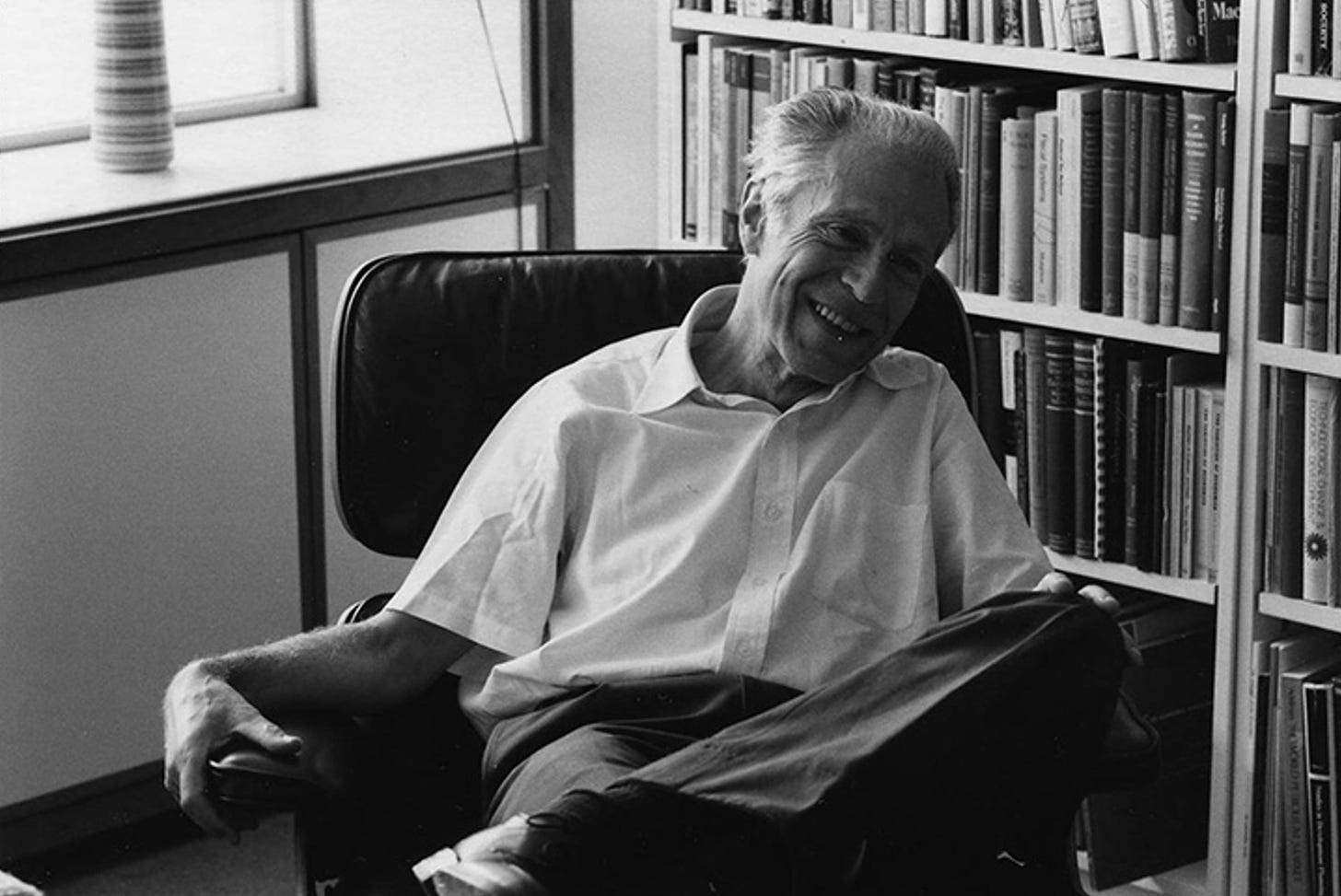

Besides driving up labor productivity, manufacturing also has a unique ability to induce forward and backward linkages. To appreciate the novelty of the concept, it is helpful to situate it in its intellectual history. The concept of linkages comes from the development economist Albert Hirschman, who, at the time, was writing against the prevailing development paradigm of balanced growth theory.7 The basic argument of balanced growth, and to use the example that Hirschman himself used, is that a shoe factory in an underdeveloped country will fail because the workers, employees, and owners will not buy all of its outputs. Meanwhile, other citizens are caught in the underdevelopment trap and won't be able to afford the new shoes. And so, the argument for balanced growth is to simultaneously start a large number of new industries so that employees of different sectors will be each others' clients.

Hirschman's critique of this approach is that it provides no mechanism by which countries can break out of this underdevelopment equilibrium. Instead, he argues that the movement from one state of development to the next occurs through a series of uneven advances of one sector followed by the catching up of others. If catching up overreaches its goal, then advances in other industries must occur. In other words, investment in one sector "induces" investment into a complementary other. The question, then, is how to identify activities to create these imbalances. Hirschman's answer is that we must choose activities with the maximum backward and forward linkages. A forward linkage occurs when investment in a project spurs investment in later stages of production, while a backward linkage arises when a project drives investment in the inputs needed for its success. Different sectors have different degrees of these linkages. Investment in projects with the greatest amount of linkages promotes development because it induces new investment.

Enter manufacturing. Compared to other sectors, the sector generates a ton of linkages. Its complex supply chain of inputs—from raw materials to machinery to various intermediate goods—encourages investment in upstream industries (also known as backward linkages). Its outputs also often serve as inputs to sectors, creating forward linkages as downstream industries expand to utilize these products in their own processes. Developing these interdependent relationships stimulates broader economic activity, induces more investment, and creates opportunities for further growth. In contrast, sectors such as agriculture or services typically have fewer linkages, as their outputs are often consumed directly or exported with minimal processing, limiting their potential to stimulate broader economic activity.

Building new state and firm capacities

Besides generating linkages up and down the supply chain, manufacturing also induces new state capabilities, or what Hirschman calls Social Overhead Capital (SOC). SOC comprises basic services without which primary, secondary, and tertiary productive activities cannot function effectively. Investment in manufacturing generates political pressure for state agencies to invest in constructing ports, railroad systems, electric power, etc. Having these state capabilities, in turn, reduces the risk of future investment in factory-based production.

Manufacturing also induces new firm capabilities, especially as manufacturing increases in scale and complexity. As manufacturing plants increase in scale and complexity, managing them increasingly involves coordinating a variety of inputs, optimizing resources through trial and error, and maintaining efficient production systems.8 This complexity forces firms to develop new capabilities, including a labor force that is disciplined and accustomed to paid labor, salaried management (a managerial elite with production capabilities in a wide range of industries and government bureaucracies), technological know-how (with up-to-date machinery), and project execution skills in both private and public sectors (a cadre of entrepreneurs with project execution skills). Like investment in SOC, these capabilities generate a virtuous loop. Investment in manufacturing generates firm capabilities and improves project execution skills. This, in turn, makes future investments in manufacturing less risky and more profitable.

Besides accelerating growth, manufacturing also has the potential to create a more egalitarian society. In contrast to the gigified and precarious employment that has become prevalent in the knowledge economy, manufacturing can bring back stable, well-paying jobs. In the U.S., for instance, the rise in income inequality has closely tracked the decline of manufacturing jobs. New research that looks at panel data for a range of countries between 1960 and 2012 also suggests that the movement of employment into the manufacturing sector reduces income inequality regardless of a country’s stage of development.9

Concluding thoughts

Having outlined why manufacturing has been such an important engine of development, the question is whether manufacturing’s pro-development characteristics still apply today, especially to countries like the U.S. and China, who are leading the charge behind the new productivist era. It would be a mistake to fetishize manufacturing’s pro-developmental characteristics in the 21st century, especially among advanced countries. Multinational corporations, global value chains, and the ICT revolution, among other developments in the capitalist economy, are new variables that may alter the sector’s economic benefits. Still, as public funding is mobilized to support a new manufacturing renaissance, it’s essential to ask if manufacturing in the 21st century still holds its developmental magic—or if other sectors are now better equipped to take on that role. That shall be the topic of another post.

This phenomenon is also known as the Solow Paradox or the IT Productivity Paradox.

Gordon, Robert J. 2017. The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living since the Civil War. Princeton University Press.

Lewis, W. Arthur. 1954. “Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour.” The Manchester School 22(2): 139–91

The Lewis model also explains how the economy goes from profiting off surplus labor to relying on the marginal productivity of labor. The model argues that when the surplus labor is exhausted, wages in the traditional sector rise, which also increases wages in the modern sector, thereby reducing profits and slowing growth. At that turning point (also known as the Lewis Turning Point), the transfer of labor from the traditional sector to the modern sector reflects differences in the marginal productivity of labor between the sectors. This eventually leads to an integrated labor market and economy. By the end of this process, when surplus labor is depleted, wages and profits are determined solely by the marginal productivity of labor.

Rodrik, Dani. 2013. “Unconditional Convergence in Manufacturing*.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 128(1): 165–204.

Hallward-Driemeier, Mary, and Gaurav Nayyar. 2018. Trouble in the Making?: The Future of Manufacturing-Led Development. The World Bank Group.

Hirschman, Albert O. 1958. The Strategy of Economic Development. 17. print. New Haven: Yale University Press

Amsden, Alice. 2001. The Rise of “The Rest.” Oxford University Press.

Baymul, Cinar, and Kunal Sen. 2020. “Was Kuznets Right? New Evidence on the Relationship between Structural Transformation and Inequality.” The Journal of Development Studies 56(9): 1643–62