The Rise and Fall of Industrial Policy

Industrial policy is back. Here's a brief intellectual history of why it went away.

Just five years ago, the term "industrial policy" would have been dismissed with disdain in mainstream economic circles. Today, it has gained broad acceptance as a legitimate and essential tool of economic policy. From the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in the US to the Green Deal Industrial Plan in Europe, governments are embracing industrial policy and applying a more hands-on role in guiding their economies. Even with Trump's reelection and his plans to dismantle the IRA and instead line the country with tariffs, his (misguided) plan is nevertheless to use state policies to strengthen domestic industry.

However, assuming that state-led industrialization is a new policy terrain is incorrect. Industrial policy—not laissez-faire—has been the historical norm for as long as countries have pursued industrialization and development. Even the US and German states employed tools like infant industry protections to shield and nurture their domestic industries during their initial phases of catchup to England.1 In development economics, the question of how states ought to intervene to accelerate industrial capacity was one of the disciplines’ motivating inquiries. Why, then, did industrial policy and scholarly commitment to it go away? Focusing on the postwar period, this post gives a brief intellectual history of industrial policy, how support for it emerged alongside the field of development economics, and how it came to be demonized within economics.

The rise of industrial policy

Development economics is a relatively young sub-discipline of economics, emerging in the 1940s and 1950s during a wave of decolonization as dozens of new states in Asia and Africa gained independence from European colonial rule. From its inception, the project of development economics was considered heretical because it contradicted a key belief in orthodox economics—that the "laws" of economics operated in the same way no matter the country. Yet, its emergence in the post-war period was perfectly timed. The Keynesian Revolution, which itself was an attack on the economic orthodoxy after the Great Depression, established the view that there were not one but two kinds of economics. One was of the classical tradition, which applied in the rare case of full employment. The other was Keynesianism, which took over otherwise.

The new intellectual paradigm of Keynesian economics was critical for the development sub-discipline because it undermined the view that only one set of economic theories governed all countries.2 So, while the orthodox perspective saw industrialization as the product of perceptive entrepreneurs who gradually scaled production, the Keynesian revolution allowed development scholars to formulate new theories of industrialization in developing countries.

Not before long, what was agreed upon was that building up an industrial base in a developing country would require deliberate, intensive, and guided efforts by the state. What exactly these efforts entailed became the subject of debate. It is in this context that many famous development theories were formulated and debated—theories of a big push or balanced vs unbalanced growth or import substitution industrialization. Yet, despite differences in approach, the broad consensus was that state intervention and industrial policy were indispensable for achieving economic development and structural transformation.

The fall of industrial policy

By the 1970s, as economic growth lagged behind expectations across developing countries, the debate shifted from how best to do industrial policy to questioning whether it should be done at all. Part of the reason was because the sub-discipline—and its commitment to an interventionist state—came under dual criticism from liberals and conservatives.

From the left, the focus on transforming the productive capabilities of developing countries was seen by “humanists” as overly collectivist and materialist. The emphasis that the development economics discourse placed on aggregate variables such as investment, output, and labor supply, in this view, overlooked individual rights, especially where growth came at the expense of labor exploitation. Instead, they argued that improving education, health, and even human rights needed to be recentered in the development discourse.

With the waning of Keynesian economics, the bigger blow came from the economic right, which argued that development scholarship that advocated for state-led development disregarded fundamental economic principles, resulting in a misallocation of resources and failure-prone governments. The sharpest criticism of the pro-intervention discipline came from Anne Krueger, who would later serve a term as the chief economist of the World Bank.

In a 1974 article titled The Political Economy of the Rent-Seeking Society, Krueger argued that government intervention invited competitive rent-seeking activities.3 The basic premise was that when governments intervened in the economy by providing subsidies, picking winners, or (as in her example) selectively issuing import licenses, individuals and firms would devote resources to compete for these rents rather than using them productively to develop new technology or increase efficiency. Government intervention also produces beneficiaries (or victims), and those groups will organize in support of (or opposition to) those interventions and lobby for increasing the value of the gains (or decreasing the value of the losses) that flow from them. This rent-seeking consumes resources that could otherwise be directed toward more productive uses.

In a later article, written after her tenure at the World Bank, she also argued that developing countries were being mired down by unworkable government policies—most of all, policies that intervened in activities traditionally taken on by the private sector, such as manufacturing.4 Kreuger’s work on trade and economic development laid the intellectual groundwork for what became the Washington Consensus—a set of policy recommendations primarily for developing countries that encourage privatization, trade and financial liberalization, and a non-interventionist government. Industrial policy was swept off the table.

The East Asian debate

As the rest of the developing world was mired by the debt crisis in the 1980s, several East Asian countries—notably South Korea and Taiwan—underwent a rags-to-riches growth spurt. In the 1960s, South Korea’s economy was primarily agrarian and was, by all standards, a low-income country. By the end of the 1980s, it had industrialized and caught up to the early developers in the West. To neoliberal economists like Kreuger and Bhagwati, the rise of the East Asian countries was a story of deregulation and open trade—to them, it was proof of neoliberal theories. Unlike Latin American countries, where the government intervened with import substitution policies to replace foreign imports with domestic production, the East Asian countries adopted an export-led strategy and competed in global markets.

What Kreuger, Bhagwati, and other neoclassical economists overlooked, however, was that the East Asian countries also had strong interventionist states driving their export-led approach. Far from holding back development, heterodox scholars like Alice Amsden (1989) and Robert Wade (1990) showed that strategic state intervention played a pivotal role in transforming these countries from underdeveloped economies to global industrial powerhouses. In other words, their findings revealed that the neoclassical explanations for the rise of these East Asian countries didn’t match the reality.

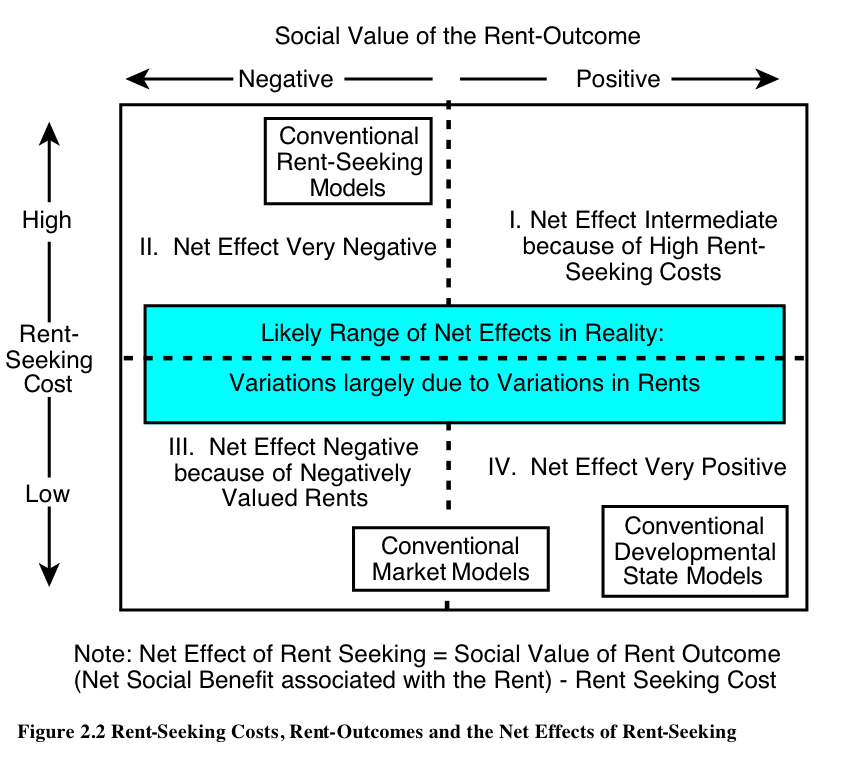

Since then, more nuanced theories about rent-seeking have been developed to explain the East Asian experience. These theories recognize that rent-seeking doesn’t always entail pure costs; it can produce both negative and positive outcomes, depending on how rents are managed and allocated.5 In the case of the East Asian countries, rents were allocated in a socially beneficial way, resulting in high growth. Learning rents, for instance, delivered rapid technological progress. So long as the costs of the rent-seeking process were less than the positive rent outputs, the net effect of the rent-seeking process could support economic growth (see figure below). In this way, rent-seeking processes in countries like South Korea were net-positive—its rent-seeking inputs were low because of the limited political factions, while its rent-seeking outputs enabled high "learning" outputs due to effective performance monitoring—allowing the country to achieve rapid growth.

However, by the late 1980s, the establishment of the Washington Consensus and the consolidation of economic thought under a neoliberal orthodoxy led to the sidelining of scholarship on the East Asian developmental state. This body of work also emerged just as the East Asian states began to liberalize and shed many of the characteristics that had made them developmental, rendering it prematurely historical. Additionally, its qualitative nature—looking closely at case studies of industrial policy implementation—was overlooked by mainstream economists who increasingly favored scientistic and quantitative approaches, further marginalizing this work on industrial policy.

Concluding thoughts

Today, industrial policy is back. But, as I show in this post, the period when it was intellectually sidelined was brief and motivated, in part, by economic developments in the Global North. The postwar embrace of Keynesian economics and development economics initially created a fertile intellectual environment for state-led industrialization, but the economic stagnation of the 1970s and the rise of neoliberalism in the 1980s cast industrial policy as outdated and inefficient. While the intellectual shift sidelined industrial policy in economic and policy circles, its implementation never truly disappeared—particularly in East Asia, where interventionist strategies enabled unprecedented growth. The history explored here shows that industrial policy was never a failed experiment—it was a contested one, sidelined not because it didn’t work but because it conflicted with the prevailing orthodoxy.

Chang, Ha-Joon. 2002. Kicking Away the Ladder: Development Strategy in Historical Perspective. London: Anthem press.

Hirschman, Albert O. 1981. “The Rise and Decline of Development Economics.” In Essays in Trespassing: Economics to Politics and Beyond, Cambridge [Eng.] ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Krueger, Anne O. 2008 (1974). “The Political Economy of the Rent-Seeking Society.” In 40 Years of Research on Rent Seeking 2, eds. Roger D. Congleton, Kai A. Konrad, and Arye L. Hillman. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 151–63. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-79247-5_8.

Krueger, Anne O. 1990. “Government Failures in Development.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 4(3): 9–23. doi:10.1257/jep.4.3.9.

Khan, Mushtaq H. 2000. “Rent-Seeking as Process.” In Rents, Rent-Seeking and Economic Development: Theory and Evidence in Asia, Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press.