Pluralism vs corporatism: why countries innovate differently

Some political systems are better at creative destruction. Others are better at creative accumulation.

Why are some countries naturally better at certain types of innovation than others? Countries like Sweden and Germany are known for their high-quality manufacturing in sectors like industrial machines, precision equipment, and motor vehicles. Meanwhile, countries like the U.S., Ireland, and the U.K. are associated with internet software, financial and professional services, and pharmaceuticals. From employment relations to competition law to financing to state policies, many factors contribute to these differences in innovation.

In this post, I’ll explore how a country’s system of interest representation—whether pluralist or corporatist—influences innovation patterns. In a previous post, I discussed this in the context of green technology adoption, highlighting interest representation as one of several factors at play. Here, I'll examine how pluralist versus corporatist systems each encourage a particular innovation pattern.

Different innovation patterns

When determining the nature of innovation—both the direction it takes and the degree of change—one of the most important factors is who is doing the innovating. Challengers to the status quo innovate differently from incumbents of the system.

In Joseph Schumpeter's first book, The Theory of Economic Development, which examines the industrial transformation of 19th-century Europe, he observed that small firms played a dominant role in the transformation of the industrial landscape. Technological progress was characterized as a continual process of disruption by which motivated entrepreneurs would improve upon production methods with new ideas, products, and processes and upend dominant players in the ecosystem. Innovation, in other words, emerged from the peripheries by enterprising individuals in a process that he called creative destruction (also known as Schumpeter Mark I). In today's world, knowledge-based, asset-light, and software-oriented sectors are considered more amenable to this pattern of innovation.

In Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy written nearly a decade later, Schumpeter turned his attention to American industry in the 20th century and noticed something very different—that large enterprises with well-resourced R&D departments and capable personnel were key drivers of new technological improvements. In other words, innovation in this context came not from outside entrepreneurs as it did in the 19th century in Europe but from established incumbents. He called this creative accumulation (also known as Schumpeter Mark II). Asset-heavy sectors like high-end manufacturing and industrial/precision equipment tend to exhibit this pattern of innovation.

These differences in the pattern of innovation have become well recognized in the innovation scholarship. To explain when Schumpeter Mark I or Mark II occurs, scholars have focused on the maturity of the technology as the primary variable. The idea is that the Mark I innovation pattern occurs when the technology is new and dominant players haven’t been established yet. Mark II occurs when the technology is mature, and further innovation becomes both incremental and increasingly expensive, demanding substantial resources such as R&D, financing, and skilled employees. At this stage, only resource-rich firms can stay in the game.

However, this doesn't explain national variation in innovation patterns. If government policies can critically affect the direction of innovation within the country, then understanding the underlying political structures—specifically the system of interest representation—is essential. We turn to this next.

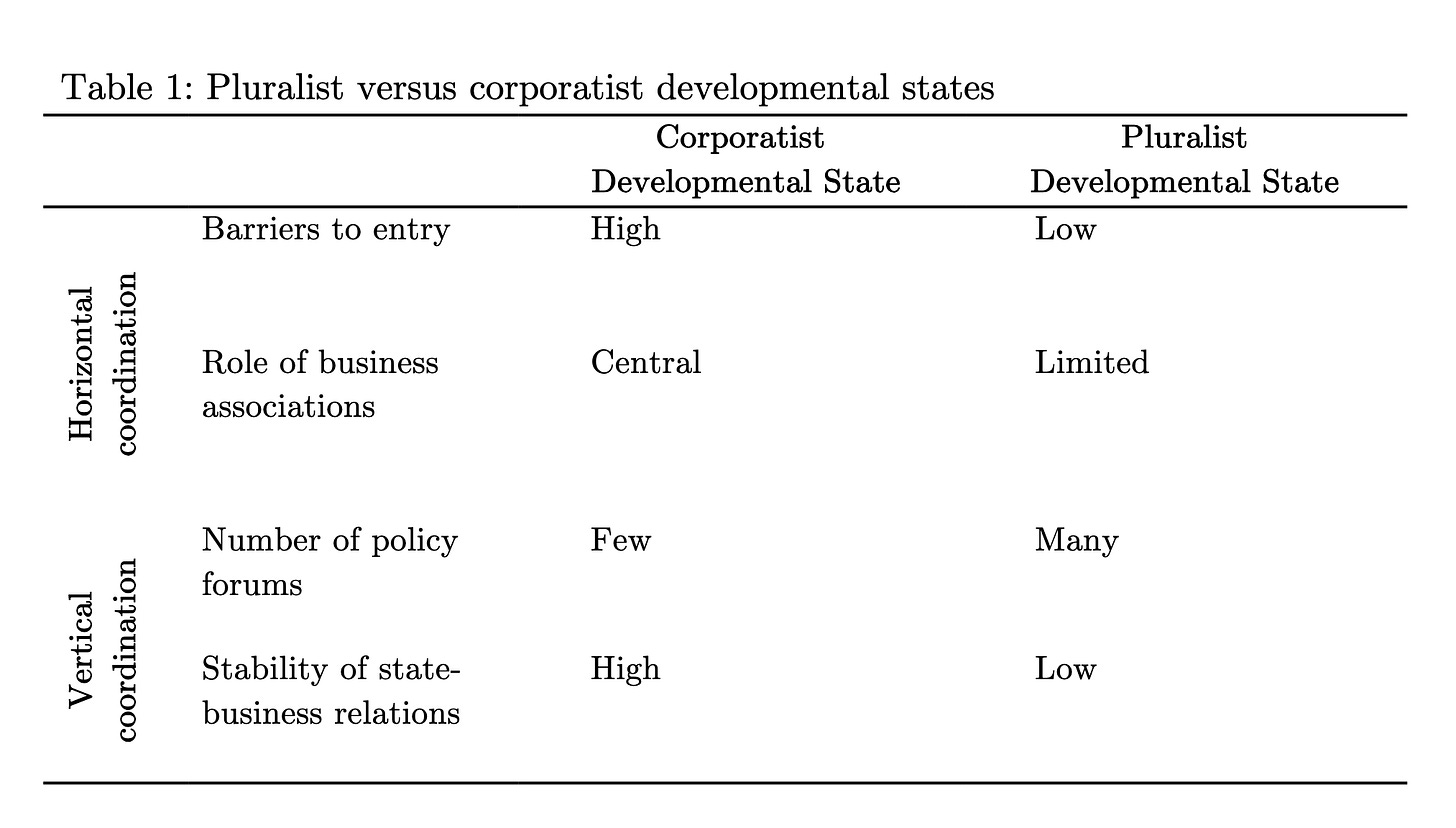

Corporatism vs Pluralism

Interest groups drive policies, so how interest groups are represented within a country is critical for understanding technology policymaking. There are two broad categories for interest representation: corporatism and pluralism.

Corporatism exists in countries like Germany, Japan, and the Netherlands. It comprises non-competitive, compulsory, hierarchically ordered, and state-recognized interest groups. In this system, each group is granted sole representation over its respective category. This gives them a direct line to state actors and the ability to influence policy decisions. Usually, however, sole representation is given in exchange for keeping demands under control and limiting the selection of leaders.

On the other hand, pluralism—found in countries such as the U.S. and the U.K.—is characterized as having interest groups organized into a number of voluntary, competitive, non-hierarchically ordered, and self-determined groups. Because these groups aren’t formally recognized by the state, they do not have sole representation of their category. This means that any interest groups, whether they are incumbents or newly formed, must battle at every policy forum to push for their preferences.1

When it comes to innovation, a corporatist system favors the innovation preferences of incumbents, making it more amenable to creative accumulation. Because constituencies have a monopoly in representation, these constituencies are, by definition, able to monopolize decisions about technological development policies and will do so in a way that protects their status as incumbents. For example, in the 2000s, Germany resisted new ICT technologies (challengers) and held on to its manufacturing core by pushing through generous social insurance policies to protect investments in manufacturing skills and extended long-term loans to insulate established manufacturing firms from market competition.2 The country was only able to push through these policies because its manufacturing incumbent had control over the country's policy forum.

Another example comes from Jonas Meckling and Jonas Nahm (2018) in their study of the German automotive sector.3 In this sector, internal combustion engine vehicle (ICEV) manufacturers are incumbents. Because of Germany's corporatist system of interest representation, electric vehicle (EV) makers who want to disrupt the industry had a much harder time doing so because their policy preferences got sidelined by ICEV manufacturers. As a result, technological development and innovation tend to be concentrated among economic incumbents, making creative accumulation the preferred pattern of innovation.

By contrast, pluralist systems are more conducive for technology challengers to succeed because policy forums are decentralized and incumbents don't have sole representation. This means that every time a new technology policy is introduced, incumbents must mobilize for their interests. This gives technology challengers an opportunity to outmaneuver incumbents. To return to the example in the automotive sector, this was precisely why policies that supported electric vehicles succeeded in pluralist countries like the U.S. and not corporatist ones like Germany. U.S. policymakers were able to intervene in the sector to promote EVs because of fluid political competition. In this way, pluralist states are better suited for creative destruction, where innovation from the periphery will tend to do better than innovation from incumbents.

Concluding thoughts

When it comes to the kind of innovation pattern that is needed for the green transition, it can be useful to think in terms of systems of interest representation. If corporatist countries are better at improving existing technologies and pluralist countries are better at supporting new disruptive technologies, then the latter would be more amenable to supporting the innovation pattern required for the green transition. This is because traditional energy firms tend to be incumbents, while green technology firms are challengers to the status quo.

However, we should be careful not to be overly deterministic. As I've emphasized in a previous writing, policymakers have agency and can design policies that generate new coalitions. This would, however, be harder to accomplish in corporatist countries where interest groups are more rigid. Still, research suggests that corporatist states can design policies to adapt to thrive in new technological domains. For example, in the 2000s, Finland and Denmark—unlike Germany—defied the traditional expectations of corporatism by entering high-tech markets.4

The system of interest representation isn't the only national factor that can affect innovation outcomes. National institutions—industrial relations, inter-firm coordination mechanisms, skill development, and financing—are also critical inputs that can shape how a country innovates. In the coming weeks, as I turn my attention to cloud computing and the automotive sector, I'll start to rely on these other national institutions to explain variation in these sectors.

See: Schmitter, Philippe C. 1974. “Still the Century of Corporatism?” The Review of Politics 36(1): 85–131.

While this approach maintained strong employment protections for regular workers, employers and trade unions in incumbent sectors cooperated to limit coverage. This resulted in growing numbers of irregular/precarious workers and labor dualization in the economy.

See: Thelen, Kathleen. 2012. “Varieties of Capitalism: Trajectories of Liberalization and the New Politics of Social Solidarity.” Annual Review of Political Science 15(1): 137–59.

See: Meckling, Jonas, and Jonas Nahm. 2018. “When Do States Disrupt Industries? Electric Cars and the Politics of Innovation.” Review of International Political Economy 25(4): 505–29.

To explain why Finland and Denmark, and not Germany, could shift away from incumbent sectors into knowledge-based industries such as biotech, software development, and telecommunications, Ornston (2012) argues that a certain development in the structure of corporatism was necessary—a new corporatist structure he calls “creative corporatism.” Under creative corporatism, the state reorganizes to invest in new supply-side resources. Trade unions, industry associations, and employers reorient their priority from things like employment protection to investing in and expanding continuing education and other human capital investments. These investments shifted the skill profile of the labor market from the skills needed in incumbent technology sectors to general skills, facilitating the movement into new knowledge-based sectors.

See: Ornston, Darius. 2013. “Creative Corporatism: The Politics of High-Technology Competition in Nordic Europe.” Comparative Political Studies 46(6): 702–29.

Very interesting post. If you were ever interested in the Marxist pespective on the question of policy, which is really a question of how the state policy is the outcome of political struggle, I'd chech out this theorization of Gramsci's Integral State by Steve Maher