Can China do industrial policy efficiently?

Not really. But that hasn’t stopped China from doing it anyway.

China has long been a heavy user of industrial policy. But just because China is doing industrial policy doesn’t mean the country is doing it well. Critics of industrial policy have argued that government intervention can result in the inefficient allocation of resources and private sector capture. What does it take to do industrial policy well? And does China have what it takes? In this post, I’ll explore a key quality needed to execute industrial policy effectively, why China lacks this quality, and why this hasn’t stopped the country from pursuing industrial policy—and achieving strong results—nonetheless.

What does it take to do industrial policy well?

To understand what effective industrial policy looks like, we must begin with South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan (known as the East Asian developmental states) in the post-war period. These countries were some of the most successful industrial policy users in recent history and were able to use it to achieve miraculous growth in the latter half of the 20th century. What made their model of industrial policy so effective?

A big part of the answer is that industrial policy was designed with the principle of “reciprocity.” Reciprocity refers to how state agencies ensured that firms did not benefit from policy favors without also contributing to broader national development objectives. The idea behind reciprocity was to tie state subsidies and incentives, such as tax breaks or cheap loans, to measurable performance metrics, particularly export performance. By doing so, governments could ensure that firms were not just sitting on rents but actively contributing to national objectives such as technological upgrading, learning, and increased productivity.

In South Korea, for instance, subsidies and cheap bank loans were explicitly contingent on a firm’s ability to meet export targets.1 These targets were not unilaterally imposed but were negotiated in high-level meetings between business leaders and the government, often with the direct involvement of the country's president, Park Chung Hee. However, if a firm failed to meet its export goals, the state would discipline it by withdrawing policy favors. This was how the private sector was kept accountable. Conditions had to be clearly defined so that firms could not weasel out of bad performance. This conditionality created a powerful incentive for firms to align their strategies with national development goals, as access to cheap capital and other subsidies depended on their ability to deliver measurable economic results.

The ability of state agencies to discipline the private sector requires certain state capabilities. State agencies must be able to monitor firms' activities, gather detailed information, and negotiate export and production targets. This necessitates strong, ongoing relationships between state and private actors. In other words, they must be embedded with business such that they stay informed about industry dynamics and can respond in ways that encourage firms to meet development goals. However, this close connection with the private sector presents a potential risk. Once the state begins providing policy favors, it becomes easier for the private sector to exploit these favors and extract benefits. In other words, state actors risk "capture" by private interests, undermining their ability to play the role of discipliner. To avoid capture, state actors need to be autonomous—but not overly so that they are entirely out of the loop of industrial development. Thus, effective industrial policy requires state agencies to strike a balance between embeddedness and autonomy.2

Does China have what it takes?

Does the Chinese government have embedded autonomy? Sort of. The extent to which the Chinese state is embedded and autonomous is complicated by the structure of the government. The typical Western characterization of the Chinese government is one of heavy centralization and top-down planning. The reality, however, is that the Chinese government is decentralized and has a loose coupling between the central and local governments.

In this setup, the central government sets the broader agenda but local governments retain significant autonomy when it comes to implementing policies and managing economic activities and can adapt central directives to fit regional conditions. While flexibility at the local level can lead to innovative and varied approaches to inducing investment, the lack of coordination across localities can create the wrong incentives for maximizing firm performance. When the central government embarks on a new development goal (e.g., setting the agenda for semiconductor manufacturing), local government officials—motivated by their own political careers—will compete to meet the policy targets set up top.

In this decentralized structure, local governments are not incentivized to discipline the firms they support and will indiscriminately supply firms with policy favors to outcompete other municipalities. As a result, firm competitiveness may not arise from developing efficient production capacities but from the generosity of a local government's policy favors. This creates an environment where regional governments rich in policy resources can outcompete those with genuinely competitive firms, so the apparent winners may not be the most economically competitive firms.

If embedded autonomy is required for effective industrial policy, then China's loosely coupled government arrangement undermines this because it separates embeddedness from autonomy. On the one hand, the central government has a high degree of autonomy, allowing it to set broad national policies and strategic goals without the influence of private interests but it has a low level of embeddedness since it seldom interacts directly with businesses. On the other hand, local governments have a high level of embeddedness since they interact directly with local businesses but they risk developing clientelistic relationships due to their lack of autonomy. This dual structure—central autonomy combined with local embeddedness—undermines the state’s ability to attach conditionality to its industrial policies.

The solar PV case

Let's look at solar PV manufacturing as an example of how industrial policy plays out in China’s decentralized government structure. It should be stated up front that the following case draws on the work of Chen Tian-Jy’s 2016 article: “The development of China's solar photovoltaic industry: why industrial policy failed.”3

Solar PV manufacturing has been the target of Chinese industrial policy for decades—as early as 1999. The loosely coupled arrangement of the Chinese government was particularly effective for inducing investment in solar manufacturing because this arrangement gave local officials a lot of leeway to adapt central directives to fit regional conditions. This influx of investment was particularly advantageous for the solar PV manufacturing sector because a critical bottleneck in the industry is attaining sufficient investment to achieve scale economies.

However, the problem with this arrangement is that it prioritizes firm size at the cost of efficiency. In China’s decentralized system, picking winners was done at the level of local government. Provincial or central governments also did not intervene when financing new firms. As a result, most Chinese solar PV manufacturers can be associated with a local city-level government sponsor. To city-level government, size was essential for two reasons. First, the larger the firm, the greater the economic activity. And since government officials’ promotions are tied to the economic performance metrics in their jurisdiction, they are motivated to enact policies to help firms grow. Second, size guarantees safety. The larger the firm, the safer it is from state predation, such as hostile takeovers or forced mergers with state-owned enterprises.

Because size was the goal, local governments were disincentivized to support firms that competed with existing firms in their portfolio. To maximize size, solar PV manufacturers adopted an aggressive capital expansion strategy. Meanwhile, local governments supported this expansion by expanding policy favors, helping with land acquisition, building infrastructure, providing utilities, securing finance, and simplifying the environmental review process. Because local governments had a growth-at-all-cost mentality when it came to their support for regional solar PV manufacturers, there was no incentive to discipline firms and withhold policy favors.

While local governments were responsible for “picking winners,” the central government was decisive in determining exit when locally sponsored firms failed. In the solar PV sector, after demand shrunk in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, many firms should’ve been forced to exit the sector, leaving only those truly competitive behind. However, the Chinese central government intervened in exit selection, bailing out only the largest firms even if they were not the most efficient because it minimized domestic economic instability.

To make its exit decisions, the central government could only rely on the information provided by its local counterparts, who were embedded and thus well-informed about the performance of local companies. However, pressures to win exit decisions incentivized local officials to overstate the capabilities of the firms they supported to the central government. As a result, embeddedness and autonomy were separated across the decentralized government structure: local governments were embedded but lacked the incentive to discipline firms while the central government was autonomous but lacked the embeddedness to make effective exit decisions.

Bad policy, good-enough results?

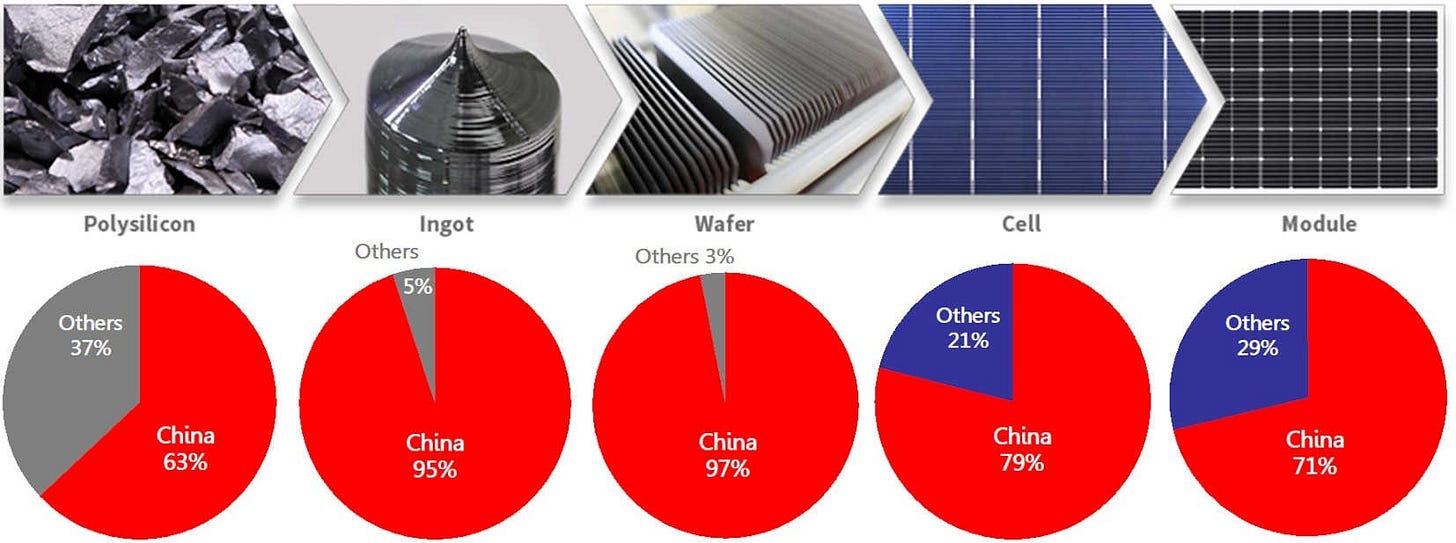

Despite China’s “bad” industrial policy, the country’s solar PV manufacturing has completely decimated global competition. Any recent chart of solar PV exports by country would show China sticking out like a sore thumb. What this should tell us is not that embedded autonomy and reciprocity are not important ingredients of successful industrial policy, but that when we don’t have the ideal institutions, we must resort to “second-best” ones. In the case of solar PV manufacturing in China, that meant drawing in massive sums of investment even if it couldn’t be guaranteed that the investment was efficiently spent. In this way, China’s decentralized and loosely coupled structure, while not ideal for effective industrial policy, was sufficient to bootstrap the country’s solar PV manufacturing sector, and eventually dominate the market.

There are two insights we can draw from this diagnosis of Chinese industrial policy. First is that "bad" industrial policy can still get us good-enough results. Second is that the lack of embedded autonomy might be contributing to the low profitability of China's solar PV manufacturing sector: Chinese solar panel prices have been in free-fall in recent years, falling some 40+ percent in 2023 alone, with many manufacturers at risk of being driven into bankruptcy. Ironically, Chinese solar PV manufacturers are now seeking government intervention to curb investment and coordinate industry collaboration to stop the price plunge. As industry demands shift from investment to coordination, so must industrial policy. The question is whether the Chinese government will have the institutional capacity to meet these new demands.

Amsden, Alice H. 1989. Asia's Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization. New York, Oxford University Press.

Evans, Peter B. 1995. Embedded Autonomy: States and Industrial Transformation. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

Chen, Tain-Jy. 2016. “The Development of China’s Solar Photovoltaic Industry: Why Industrial Policy Failed.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 40(3): 755–74. doi:10.1093/cje/bev014.

Interesting to learn how industry accountability/oversight requires a balance of embedding government in industry while maintaining gov autonomy.