Behind the AI Arms Race: U.S. vs. China Cloud Computing Comparison

Firm ownership structure and industrial policy are critical yet under-discussed differences between the American and Chinese cloud sectors.

This week's post is a little different. First, it's a deep dive into a specific aspect of one industry. Second, it's a collaborative post. Over the winter, I had the great pleasure of meeting Grace Shao, an acute AI analyst and founder of AI Proem where she shares terrific insights on AI development. She has years of experience working among the tech giants in China, including Alibaba, PayPal, Kuaishou and more. She started her career as a tech/ business reporter and has returned to her roots, focusing more on writing and content creation. She's recently put out a few bangers on the infrastructure driving AI development that I'd highly recommend. Please check out her newsletter!

What is the Cloud? And Why is it Important?

The cloud isn’t just a silent partner in the AI boom—it’s the engine driving it. Without the robust compute infrastructure made possible by the cloud giants, today’s most advanced AI models wouldn’t exist, let alone reach millions of users worldwide.

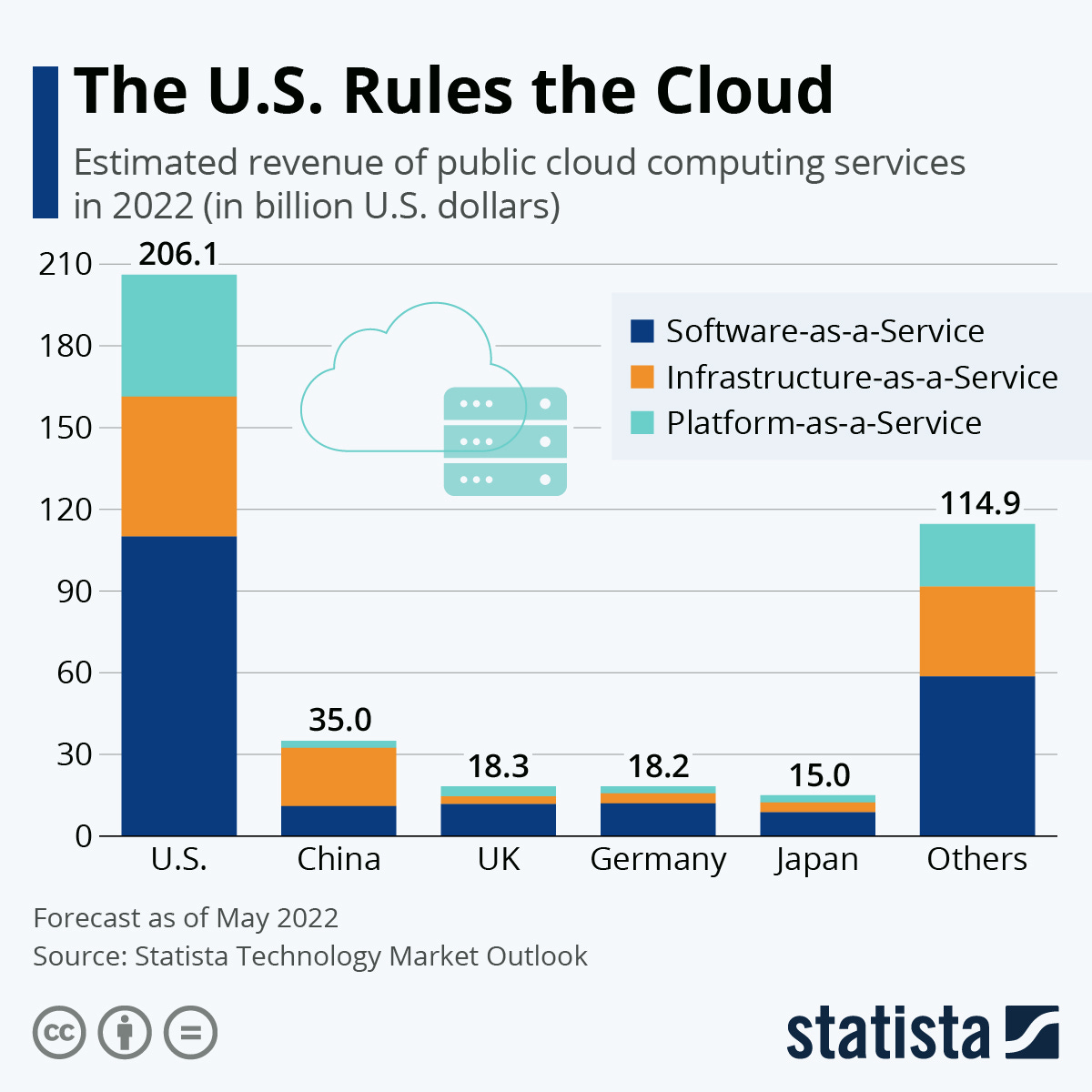

Cloud computing is dominated by the U.S. and China, making American and Chinese firms the only viable contenders in AI development. Yet cloud computing in the U.S. and China has long preceded the AI boom and has evolved in different ways. To understand the present and future of AI, we first need to unravel the story of cloud computing—how it evolved, how it differs across these two tech markets, and why it’s now the bedrock of the AI era.

Cloud computing is essential for AI because it provides the digital infrastructure to train advanced AI models. When researchers and engineers create AI models, they need access to vast amounts of computational power. This is where cloud computing comes in. It acts as the interface between high-performance GPU chips and the complex code that trains the models. For example, OpenAI trains its models on Microsoft’s cloud (Azure).

Cloud computing also plays a crucial role in deploying AI models for practical use by individuals and businesses. Once a model is trained, it needs to be hosted somewhere so users can access it. In some cases, models can live directly on “edge devices” such as cell phones (but are constrained by the computational power of the device). More commonly, AI models are deployed on the cloud and made available over the internet, enabling users and other businesses to interact with them, whether it’s through chatbots, image generation tools, or recommendation systems.

The public cloud existed long before generative AI became mainstream—as early as 2006, in the case of Amazon. Cloud firms are uniquely positioned to train and operationalize AI models because the cloud business model requires them to aggregate computational resources to rent out. This aggregation makes cloud providers uniquely positioned to dominate in the AI era.

But not all clouds are created equal. This post examines the cloud computing sector in the two countries from a comparative perspective, focusing on differences in corporate governance, industrial policy/state-business relations, and infrastructure.

Leading Cloud Service Providers in the U.S. and China

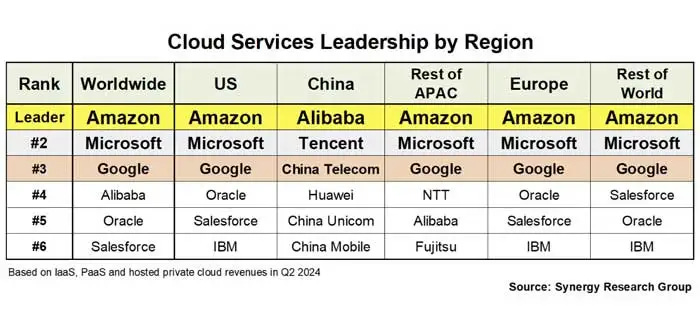

The leading cloud providers in the U.S. are Amazon, Microsoft, and Google, in that order. Amazon started to develop its cloud services in the early 2000s, launching its first cloud storage (s3) in 2006. According to Wang Gufen, Huawei formed its cloud division as early as 2005, making it one of the earliest entrants in the space in China. Despite starting at similar times, Amazon—and U.S. firms—have soared ahead of its Chinese counterparts. Today, the U.S. dominates the cloud, with China trailing as a distant second and the U.K. following as an equally distant third.

The U.S. cloud ecosystem is dominated by software incumbents. By contrast, China’s cloud providers have more diverse competencies. The telecom SOEs are hardware-first companies with strengths in telecommunications infrastructure. Huawei is traditionally strong in hardware but has also become a formidable software giant in recent years. The company has created a comprehensive ecosystem and has long invested in cloud, hardware, and various touchpoints with enterprises and consumers (far before AI became hot).

In fact, among the Chinese players, the interesting breakdown is in their clientele. Alibaba, the once big-tech darling, mostly did things the “capitalist” way and provided services to those who could pay, in this case, the large corporations. While most of Huawei Cloud’s largest customers are state-owned enterprises in China (SOEs), many people say it's mostly a result of the buyer’s choice, given Huawei’s unique hardware-software integration and advanced safety features that the company often highlights.

Looking at the bigger picture, the U.S. cloud service providers have captured the majority of the Western market, and companies like Huawei and Alibaba have focused on growing their businesses domestically and in emerging markets. This has made them competitive providers across APAC, EMEA, and LATAM (essentially ex-Western markets).

Still, Amazon, Microsoft, and Google remain the preferred cloud providers in most regions worldwide (see the figure below) and have performed well in the Chinese market as well.

Ownership Structure and State-business relations

In the U.S., the cloud is dominated by publicly traded giants like Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud, which operate under traditional corporate governance models typical of publicly traded companies to optimize capital and shareholder return. In contrast, China's cloud computing landscape reflects a more diverse set of ownership models involving publicly traded firms, private firms, and state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The leading cloud service providers are still private firms, with Alibaba Cloud, Tencent Cloud, and Huawei Cloud being the biggest players. Now, the cloud businesses of Alibaba and Tencent are set up as business units under parent companies and are publicly listed in the U.S./ Hong Kong, while Huawei remains privately owned. Following the pack are China Mobile, China Telecom, and China Unicom, which are SOEs and China’s largest traditional telecommunications providers.

Since cloud computing is an extremely capital-intensive, low-margin endeavor and different ownership structures have varying abilities to raise and deploy capital. In the U.S., for instance, publicly traded cloud firms are bound to shareholder expectations. Still, their high valuations enhance their financial credibility and flexibility, allowing them to access capital more easily. Moreover, Amazon, Microsoft, and Google are all cash-rich firms and have funneled savings from their dominance in other sectors (e.g., online retail for Amazon) into their cloud business.

Privately held companies like Huawei allow it to focus on strategic or national goals without the immediate need to satisfy external investors. Similarly, SOEs are shielded from shareholder scrutiny. In China’s case, SOEs often also benefit from government backing and policy support, facilitating large-scale investment in critical infrastructure. And the relationships between state support and companies often go beyond financial funding and resource allocation support; they extend into providing the right connections, “guanxi,” and even client-sourcing support. In these ways, China cloud firms, which are less cash-rich than the U.S. tech giants, benefit from these ownership models that allow for long-term, worry-free strategic investment.

Whether privately owned, publicly listed, or state-controlled, these different ownership structures also reflect the nature of state-business relations in each country-context. In the U.S., the state does not play an active role in directing the direction of cloud innovation nor the coordinating players within the cloud ecosystem. The extent of the state intervention is acting as a major client. Since 2016, tens of billions have been funneled into cloud provider’s coffers from various U.S. agencies. While being a client can hardly be characterized as state intervention, these large state contracts guarantee the demand for cloud service, thereby reducing the risk of investment by cloud providers.

By contrast, state influence in China’s cloud sector extends to a broader range of activities. The state provides financing (both as a customer and via subsidies) as mentioned, but it also plays a vital role in policy encouragement. It has actively planned the expansion of China’s cloud computing industry and directed the activities of private sector players. As early as 2010, the state launched its first initiative to encourage the development of cloud capabilities and to build out data centers for cloud computing. In the 13th Five-Year Plan for Economic and Social Development, issued in 2016, the state listed cloud computing as a key field encouraging more investment in the sector. In the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021), the party continued to emphasize cloud computing as a technological priority. Following the central government’s lead, local authorities have followed suit, launching new initiatives to attract investment in cloud and bolster its development. These policies showcase the state’s long-term commitment to supporting cloud computing.

Eastern Data Western Computing

This brings us to a key policy that was introduced in 2020, the “Eastern Data Western Computing” initiative. It is a national effort backed by five federal-level agencies, including the National Development and Reform Commission (the key agency that sets the agenda for the nation’s economic planning), which Sinocities lay out the details of here.

The ambitious planning strategy (which Grace has written about here) is perhaps the state’s most ambitious intervention into the cloud industry thus far. The project aims to reshape China’s digital infrastructure landscape, addressing the growing demand for computing power in the economically thriving eastern regions while leveraging the abundant renewable energy resources and uninhabited land found in the western regions.

The plan's specifics involve constructing eight computing hubs and ten data center clusters to facilitate a balanced distribution of computing power across China. Its goal is to create an integrated national system of data centers that enhances the planning and intelligent scheduling of computing resources. The ultimate goal is to transfer data generated in eastern China—home to its major industries and dense population—to data centers in the resource-rich western provinces, and it came about because most of China’s data centers are currently located in the East, along the Eastern coastlines, where urbanization is much more developed. However, those data centers are becoming increasingly costly and difficult to maintain. Lack of access to renewable energy also means many of these data centers rely on fossil fuels, contributing further to pollution and climate change.

To break it down, the basic idea behind the concept is to leverage the resource-rich western province for computationally expensive tasks that do not require proximity to users. Consider rendering a feature-length animation. Rendering is a highly demanding process in terms of computational power, but it only needs to be done once. Once the animation is rendered, it can be distributed without requiring further heavy computation. In contrast, streaming that animation to viewers is an entirely different type of task. Streaming doesn’t require significant computational power—instead, it demands low latency and high data throughput to ensure a smooth viewing experience. Therefore, streaming services need to be handled by data centers that are geographically close to end users.

AI has a similar logic. Training an AI model requires massive computational resources that don’t need to be performed near the end users. Model training can take days or even weeks, but once completed, the model is ready for deployment. The idea behind the Eastern Data Western Computing initiative is to allow these training tasks to be offloaded to data centers in resource-rich, remote regions where land, energy, and cooling are more readily available and cost-effective. By contrast, inferencing an AI model, like streaming an animation, requires low latency to provide a seamless user experience. So, they must be handled by data centers close to users (mainly on the eastern coast) to minimize lag.

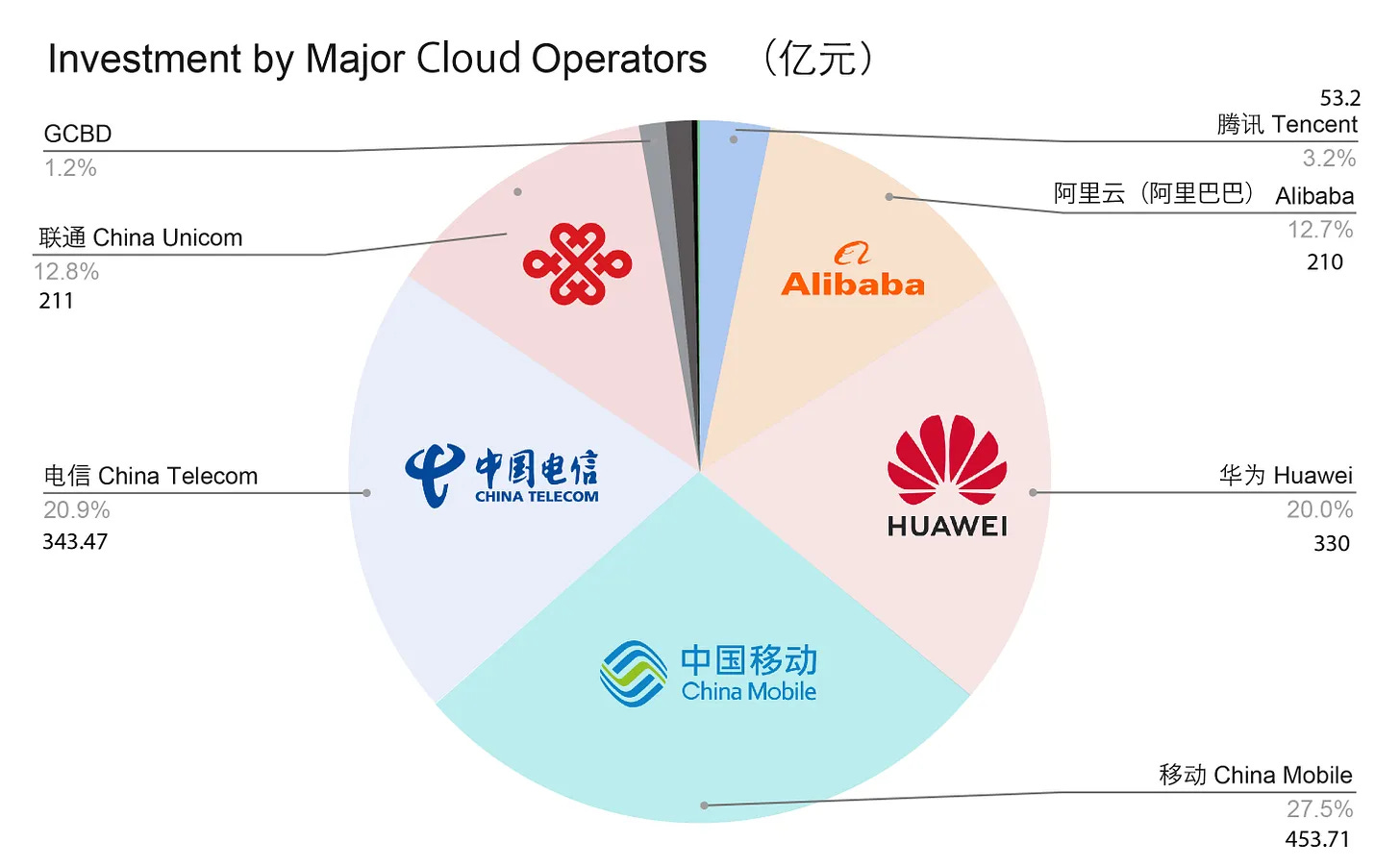

While it's too early to assess the plan's impact, it is clear that national-scale coordination across the various players is key for its success. And, to a large extent, what makes this coordination possible is the fact that China’s cloud ecosystem isn’t comprised solely of publicly traded private firms (as well as firms that have core competencies in hardware and not just software). Unsurprisingly, the two largest investors in the plan are SOEs—China Mobile and China Telecom—based on the research of Sinocities. Privately held national champion Huawei is a close third. Alibaba and Tencent—publicly traded and disciplined by short-term profits—are considerably smaller investors in the plan.

Source: Sinocities

China’s Energy Advantage

As mentioned, China’s ability to coordinate across public and private sectors and push ahead with one agenda has been a major catalyst to its has been a major catalyst to its economic success that we’ve seen over the last four decades that we’ve seen over the last four decades.

In 2014, Guizhou was established as the National Big Data (Guizhou) Comprehensive Pilot Zone to create a national-level cluster for the development of the big data industry. By 2022, the province was already providing services for the likes of Huawei, JD.com, Alibaba, Tencent, and Foxconn, as well as leading international companies such as Apple, Microsoft, Hewlett-Packard, and NIIT. Its speed is unparalleled, and in just under a decade, there have been. Its speed is unparalleled, and in just under a decade, there have been over 23 key data centers in operation or under construction in the province, including eight ultra-large ones, making it one of the world's most concentrated regions of ultra-large data centers.

This coordination, however, extends beyond the computational stack and into energy infrastructure. The last ten years of investment by the state in renewable energy are paying off, as it plays a crucial role in powering China's energy transition at large. It is now also powering a critical sector—the burgeoning data center landscape. While coal remains a significant part of China's energy mix—accounting for about 60% of electricity generation—national orders will move to greener sources in 2025.

China’s infrastructure advantage also leans into its competitive electricity prices, which has positioned it well to get a head start on this front. Western regions such as Shanxi and Guizhou offer some of the lowest industrial power rates globally, providing a significant advantage over countries like the United States, which is facing major power shortage concerns and rising energy prices.

By coordinating efforts across sectors—energy production and data center development—China is capitalizing on its renewable resources to support increasing demands for computing power and artificial intelligence. This approach is a strategic move to promote sustainability and address regional disparities in computing capacity, as it has also been proven to work in the initial stages of the renewable energy infrastructure build-up.

Still, it's important to take a step back and see the bigger picture. While Chinese cloud firms have permissive ownership structures that allow for closer state-business relations, data center deployment in China still lags behind that in the U.S. China’s top-down strategy has been proven to be efficient when ramping up an industry, but whether it is enough to compete head to head with the U.S. remains to be seen.

An important piece on something I think a lot about. I will be coming back to this.